From Working Code to Maintainable Code

When I was learning to code, the goal was simple: make it work. In school projects or small personal experiments, once the program ran and produced the expected output, it felt like the job was done.

After a while, though, that wasn’t enough anymore. I started wanting to write code that wasn’t just correct, but better. So I began reading articles, blog posts, and books about “good code” and “clean design”, hoping to find clearer guidance.

What I found instead was a lot of rules.

“A function should never be more than 10 lines.”

“Variable names should be as short as possible.”

“Always do this. Never do that.”

And I kept stumbling on the same question: why?

These rules sounded confident, but they rarely explained what problem they were actually solving. Sometimes following them made the code clearer. Other times, it felt arbitrary or even made things harder to understand. I couldn’t find a simple, shared definition of what better code really meant.

At the same time, as I started working on larger systems with other engineers, I noticed something important: even when the code worked, coming back to it later was often confusing. Small changes would break things unexpectedly. Features that sounded simple turned out to be surprisingly hard to implement.

That’s when I started realizing that writing code that works isn’t the same as writing code that lasts.

This is where the idea of complexity enters the picture.

“Complexity is anything related to the structure of a software system that makes it hard to understand and modify the system.”

— John Ousterhout, A Philosophy of Software Design (2018)

That definition helped me see something more clearly: “better code” is fundamentally about managing complexity.

Most of the rules I had encountered about function length, naming, structure, or duplication suddenly made more sense when viewed through that lens. They aren’t universal truths. They’re heuristics meant to keep complexity under control. When they succeed, code becomes easier to understand and modify. When they don’t, blindly following them can actually make things worse.

A function isn’t “bad” because it has more than ten lines. A variable name isn’t “good” because it’s short. These choices only matter in terms of how they affect the structure of the system and the mental effort required to work with it.

So the question I try to ask now isn’t “am I following the rules?” but:

does this decision reduce complexity, or does it add to it?

This article is built around that idea. It’s an attempt to look at everyday code through the lens of complexity, and to argue that writing better code isn’t about memorizing guidelines, but about consistently making design choices that keep systems understandable, adaptable, and resilient over time.

The Cost of Ignoring Complexity

At first, complexity doesn’t seem like a big deal. The code works, the tests pass, and features get shipped. But slowly, things start to drag. Small changes take longer. Bugs are harder to fix. New team members or even future-you need more time to understand how things work.

These issues don’t show up overnight. They creep in. But if you pay attention, there are early signs.

Change Amplification

Sometimes, making a small change in one place means updating five other files, multiple tests, and maybe even other services. A simple rename turns into a mini refactor.

This is called change amplification, and it usually means parts of the system are too tightly connected. It makes even safe changes feel risky and slows everyone down.

High Cognitive Load

When things are too coupled, full of edge cases, or just hard to follow, it takes a lot of mental effort to get started. That’s what people mean by high cognitive load: you have to keep too much in your head at once.

Unclear Change Points

A bug shows up in one place, but the root cause is somewhere else. Or a new feature needs to touch several parts of the code, and it’s unclear which one should be updated or whether something new should be introduced.

Habits That Help Manage Complexity

I’m still learning, but these habits consistently help reduce complexity or at least keep it under control.

Keep Boundaries Clear

Even in small projects, boundaries matter. A function should do one thing. A module should have a clear responsibility.

When boundaries get fuzzy, everything becomes harder to change later.

Read Code to Understand Design

When working in an unfamiliar part of the codebase, I try to slow down and ask: why is this written this way?

Not just how it works, but what the intent might have been.

Doing this regularly helps build intuition for what “clean” or “messy” really means in context.

Understand Tradeoffs (Not Just Rules)

Advice like “keep functions short” or “don’t repeat yourself” can be useful. But followed blindly, these rules can increase complexity instead of reducing it.

Most design decisions are tradeoffs. It’s not about always doing the same thing it’s about understanding the consequences.

One question I ask myself more often now is:

will this make the next change easier, or harder?

Complexity Is a Design Problem

One of the most important lessons I’m learning is that complexity rarely comes from “bad code”. More often, it’s the result of reasonable design decisions made under pressure, with limited context, or based on the best information available at the time.

Code grows around real-world constraints: deadlines, changing requirements, evolving teams. Sometimes the structure doesn’t keep up.

Complexity, then, is usually a design problem, not a personal one. It’s about how pieces fit together and how early decisions shape everything that follows.

Strategic vs Tactical Programming

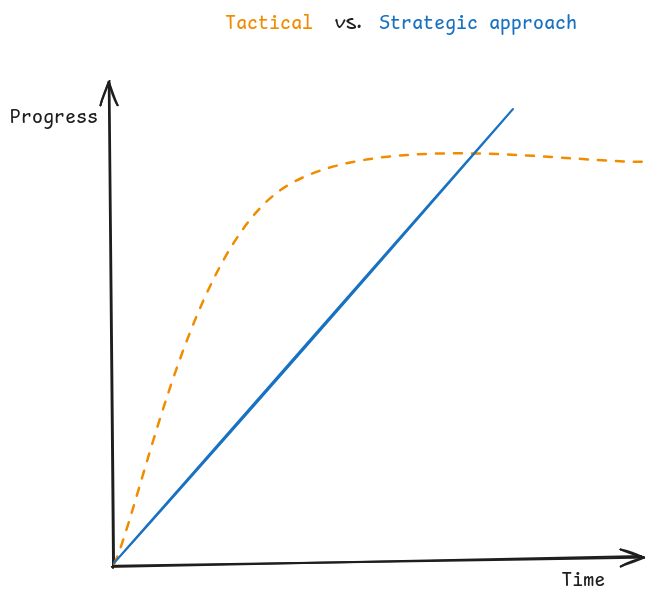

If better code is about managing complexity, then another useful distinction appears: tactical versus strategic programming.

Tactical programming focuses on the immediate problem. The goal is simple: make the change work. The solution might be tightly coupled or awkwardly placed, but it fixes the issue and lets you move on.

This approach aligns naturally with rule-based thinking. Under pressure, it’s tempting to apply whatever guideline seems to solve the problem quickly without stepping back to consider its impact on the system.

Strategic programming, in contrast, treats every change as a design decision. Instead of asking “how do I fix this?”, it asks “how should this fit into the system?” The focus is on boundaries, responsibilities, and preventing complexity from accumulating.

The difference is where the effort goes.

- Tactical programming minimizes effort now

- Strategic programming minimizes effort over time

This is why complexity grows quietly. Tactical fixes feel efficient in the moment. Each one adds a small amount of structural friction rarely enough to justify stopping. But over time, they lead directly to change amplification, high cognitive load, and unclear change points.

Strategic programming often feels slower because it requires extra work up front renaming things, moving code, reshaping abstractions before adding new behavior. Under deadlines, that cost is easy to skip. Over time, though, it’s what keeps a codebase understandable and adaptable.

Managing complexity means choosing when to be strategic. Not every change needs redesign but without regular strategic decisions, systems inevitably drift toward fragility.

In that sense, better code isn’t about following rules.

It’s about consistently favoring strategic choices that reduce complexity instead of tactical ones that merely hide it.

Final Thoughts

Complexity isn’t something you eliminate once and for all. It’s something you manage continuously.

Every change either adds a little friction or removes some. Every design decision either clarifies the system or makes it harder to reason about. Over time, those small choices matter more than any single rule or refactor.

I’m still learning how to make those choices well. But framing “better code” as a question of complexity rather than correctness or style has given me a much clearer way to think about design, tradeoffs, and long-term maintainability.